Nationalist Foreign Relations – A History, Part 5

This is the final installment of the series “Nationalist Foreign Policy – A History”. Please click on the menu item above to see previous installments.

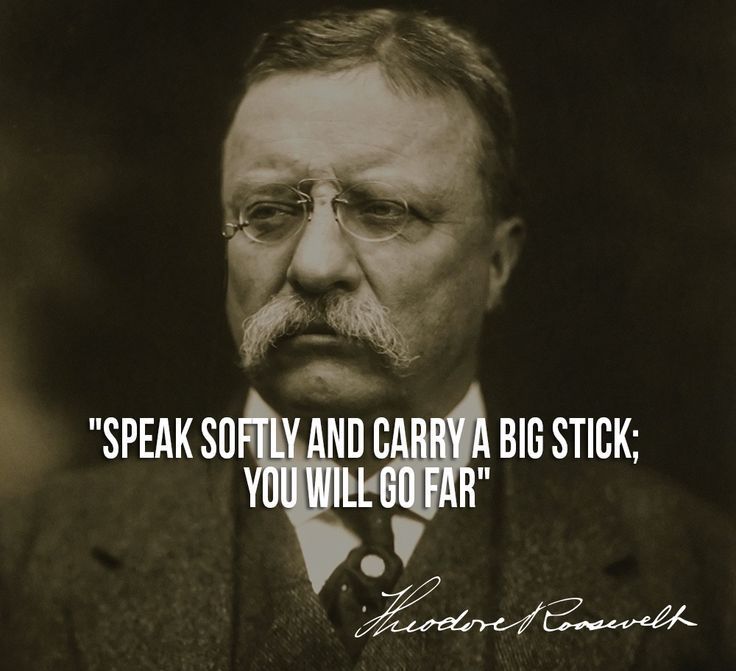

Theodore Roosevelt coined his famous maxim when Great Britain still dominated the world through its mastery of the seas and colonial empire. At the same time, Roosevelt had the foresight to recognize the world was becoming increasingly multipolar with the United States, Germany and Japan becoming regional hegemons in the Western Hemisphere, Europe and Asia respectively. Both adroit diplomacy and a newly invigorated navy and armed forces would be necessary to preserve America’s national security and way of life in the coming new world order.

Today America fills the role of a great world power watching its influence wane in an increasingly multipolar and nationalistic world. This new world order consists not only of regional hegemons like China, but also non-state actors as diverse as multinational corporations, international non-profit advocacy groups and terrorist organizations. This proliferation of powerful actors and the variety of weapons available to them multiplies both the risk of conflict and the arenas in which conflict can occur. Wars can now be fought in outer space, cyberspace and the trade and migration spaces. The US cannot waste its advantages in soft, hard and economic power if it expects to remain secure and a beacon of freedom in this newly competitive world.

“Speaking softly” in such a world should be based on a policy of realism and restraint that respects other nations’ cultures and interests and vigorously defends our own only when it is directly in danger. The Center for Strategic and International Studies’s recent paper “Getting to Less” surveys the various theories for achieving this, two of which stand out – offshore balancing and command the commons. As further described in this article by Harvard Professor Stephen Walt, offshore balancing relies on local powers in a region to keep the peace with America intervening only if they are incapable of opposing a potential hegemon. For example, while it is in our direct national security interest to prevent Russian hegemony in Europe, our commitment to NATO can be scaled back since Western Europe has the capacity to defend itself against Russian aggression. We would intervene only to counterbalance against any temporary Russian advantages, echoing TR’s balancing intervention in the Moroccan crisis. Realist offshore balancing would also call for military withdrawal from the Middle East, though we would watch in “splendid isolation” in case any nation like Iran was achieving hegemony.

Meanwhile, the “big stick” of a realist foreign policy would be the “command the commons” approach, in which the US would defend itself and project power through dominance of the air, space, cyberspace and seas. Preserving the dollar as the world’s reserve currency would also help continue American hegemony in the commons of international finance. While America already is a great power in these arenas, we will need more investment in our Air Force, space program and cyberdefense capabilities to maintain it. Finally, Roosevelt’s beloved navy would need to be expanded to the 350-ship size that has been discussed for years.

We also must remove important domestic barriers to a realistic and restrained strategy. American globalists have essentially privatized trade and immigration policy for their benefit and thus removed two important levers for responding peacefully to international conflict. This makes armed conflict more likely. Our lax immigration laws also make us vulnerable to the use of mass migration as a weapon (cf. Syria and Venezuela) and multilateral trade agreements prevent us from hardening our economy from trade disruptions and dumping. The federal government should reclaim power over these policies and return them for use in the national security toolbox.

While our military and economic power is formidable, America’s soft power of freedom and democracy has always been our most effective form of international influence. America’s mere existence is a threat to regimes like China and Russia and we must remain strong to deter their attacks. However, for America to be strong, the American people must be strong. Dealing with our serious social and economic challenges by guaranteeing them a “square deal” in their lives would be the most effective way to assure our long-term security.

As a veteran himself, Roosevelt was proud that no American soldier or sailor died during his presidency. He achieved this with a policy where diplomacy was primary and military intervention a rarity. In today’s nationalist world, a modern Rooseveltian foreign policy would draw on our historic respect for diversity to develop a policy of respect for the similar diversity of nations and confine conflict, both peaceful and military, to serious dangers to our national security and way of life. Multilateral organizations would be an important means, but not an end, in this strategy. A sustained commitment to such a realistic and restrained strategy would preserve our independence and freedom in the 21st century while maintaining America as a beacon of freedom and hope for the rest of the world.