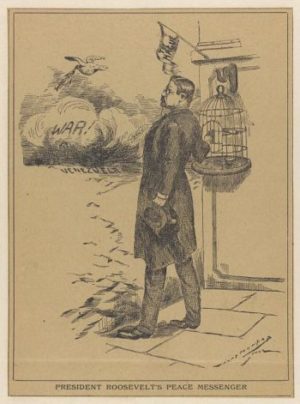

I am insisting on nationalism against internationalism.

Theodore Roosevelt in a letter to Sen. Albert Beveridge

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the globalist’s worst nightmare. Nations scrambled to protect their own citizens first by ensuring that medical supplies and other essential items stay within their borders rather than be traded to the highest international bidder. It should never have been this surprising. Even the apostle of globalization Thomas Friedman foresaw this in his paean to globalization “The World is Flat”, when he identified a pandemic as one of the dangers that could halt the phenomenon he praised so effusively.

In fact, the pandemic is actually a stress test revealing the endurance of nationalism as the true basis of international relations. Rather than inevitably leading to war, a nationalist-based foreign policy can create as stable a world as globalism while also preserving its diversity of cultures. But how do we get there? This post will begin a series on the history and background of nationalism and the models it provides to achieve the common goal of peaceful international relations.

Origins of Modern Nationalism

Nationalism is hardly a recent phenomenon. Next to the family, nations are the oldest form of human community. They arose out of the need to band together for safety and maximize efficiency by encouraging specialized skills. Nationalism could take the form of nomadic tribal loyalty or simply a commitment to one’s neighbors in a local village or city-state. Eventually, the ties between the members became based on a shared perception of a common ethnicity or culture, enabling them to easily identify in and out groups. National rivalry and conflict inevitably resulted from these distinctions and has defined much of human history.

Read against this reality, it is easy to dismiss globalism as simply the modern elite’s commitment to hope over experience. In fact, Western globalism has deep roots and can be traced back to the Roman Empire and the establishment of the Roman Catholic Church. The Romans knit numerous nationalities into a unitary state based on the rule of law that continued in some form for almost two millennia. To Europeans, the Roman world became synonymous with peace and unity. It’s pull on the Western psyche is illustrated by the fact that, after the fall of the original empire in 476 AD, the first successful king of Europe Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800 AD and a Holy Roman Empire lived in central Europe until the 17th century. Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire survived and often dominated the Middle East until it’s fall in 1453.

After the fall of Rome in the fifth century, the most successful globalist institution in the Western world was the Roman Catholic Church. In the medieval world, it held not only religious power, but claimed territory and temporal power over rulers. Its theology taught that all Christendom was to be united in peace under the twin pillars of Empire and Church, though the Church was to be predominant. In fact, this peaceful unity was rarely, if ever, achieved, The emperor’s power declined until he became only a titular ruler over the dukes and kings of what later became Germany and Austria. In an historically accurate gibe, it was said that he became neither holy, nor Roman, nor an emperor. The Church’s power also was increasingly challenged by medieval and Renaissance rulers. Despite all this, the idea of a unified religious and secular Christendom survived in local and international law.

The dream of any such unity came crashing down during the 17th Century, when the Holy Roman Empire itself was racked by a brutal religious war between Catholic and Protestant rulers. Known as the Thirty Years War, it remained the deadliest war in European history until World War I. While fought officially by kings and dukes, it was really a religious war fought in the name of Catholicism and the various Protestant denominations adopted by local rulers. In other words, it was essentially a war between two sets of globalist, transnational institutions.

The exhausted warring powers finally ended the conflict in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, which created the modern system of international law and relations. Since globalism caused the war, the treaty established the nation-state as the bulwark for keeping the peace. The treaty vested religious and secular power in sovereign states and officially ended the Catholic Church’s claim of transnational authority. States were defined as those entities that had effective governments that ruled within territorial boundaries. While Europe was no stranger to war in later years, the Westphalian system avoided the indiscriminate killing of the Thirty Years War for over two centuries afterwards.

The French Revolution and resulting Napoleonic Wars brought back memories of the dangers of globalism to Europe. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the victorious powers in that war re-established the old system of nation-states, which managed to keep the peace until the beginning of the twentieth century. The horrors of the two world wars then caused national leaders to question the nation-state as a peace-keeping model and revived globalism as a potential solution. The failures of this solution will be the subject of the next post.