OR HOW A GOOD PEACE STRATEGY WENT HORRIBLY WRONG

Nationalist Foreign Relations – A History, Part 3

As things are now, such power to command peace throughout the world could best be assured by some combination between those great nations which sincerely desire peace and have no thought themselves of committing aggressions. The combination might at first be only to secure peace within certain definite limits and on certain definite conditions; but the ruler or statesman who should bring about such a combination would have earned his place in history for all time and his title to the gratitude of all mankind

Theodore Roosevelt, Nobel Prize Lecture, May 5, 1910

Theodore Roosevelt’s quest for peace has been a goal of mankind since the beginning of time. Three different theories have been proposed to achieve it. The first is the simplest and most radical – world government. This is the globalist solution and springs from old memories of the Roman Empire’s rule of what in Westerner’s minds was the “known world“. The second is the more practical balance of power approach described in my previous post and followed by the European powers in the 19th century.

After World War II, a new strategy known as functionalism concentrated on developing international arrangements to share discrete public sector responsibilities such as collecting meteorological data, coordinating air traffic control and similar uncontroversial areas. Sometimes referred to as “peace by pieces“, the central feature of this approach was the creation of international agencies with limited and specific powers. Functional agencies could operate only within the territories of states that choose to join them and therefore would not directly threaten state sovereignty. In theory, the web of agreements would eventually become so strong that nations would wake up one day and realize that they could not afford to go to war against each other.

Even in the midst of the Cold War, functionalism became the primary working theory of international relations and created useful mechanisms for nations and the public. For example, the Universal Postal Union enables you to send a letter to any member nation for the price of a first class stamp in your home country. I previously highlighted the work of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation as a good example of how transnational efforts can complement rather than threaten national sovereignty. In their early days, United Nations specialized agencies such as UNICEF, the World Meteorological Organization and even the World Health Organization performed useful functions. The original European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) formed in the 1950s stretched the bounds of the functionalist model, but found early success because of its limited goal of reviving the European steel industry and the jobs that came with it.

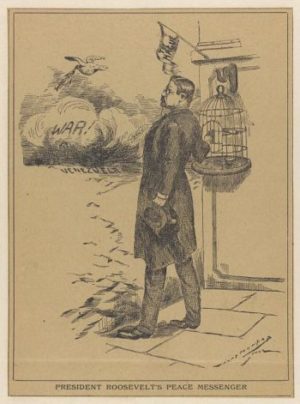

An ardent American nationalist, Theodore Roosevelt arguably helped develop the tenets of a successful functionalism. As the above quote indicates, TR favored international arbitration and agencies, but believed their jurisdiction should be limited and confined to disputes among great powers who had the strength to insure the limits were respected and the results properly enforced. For example, he signed treaties to submit future disputes with Canada and Great Britain to arbitration, but specifically excluded territorial disputes from their reach. He was furious when Woodrow Wilson abolished this exception. TR also opposed the League of Nations not because of a belief in isolationism, but because he believed it would be either impotent or would submit the United States to the whims of smaller, less important nations. History would eventually exonerate his assessment.

The concept of functionalism began to be abused in the 1970s when international agreements were no longer confined to discrete subjects that were openly negotiated and narrowly defined. Instead, broad grants of power were made to multilateral organizations run by elite bureaucracies unresponsive to the public who made rules with little notice or opportunity for meaningful public input. It was not surprising when these bureaucracies succumbed to the institutional imperative. Instead of simply solving the original problem, they worked to identify new problems in order to perpetuate the organization or ideal. Thus, the limited goals of the ECSC were slowly and deliberately expanded over the decades until it became the European Union with the goal of creating a United States of Europe. Similarly, the process of bilateral negotiation of specified tariff reductions metastasized to become the World Trade Organization with a new goal of eliminating non-tariff barriers. This eventually led to the creation of private dispute resolution courts in agreements like NAFTA. The result was a globalist’s dream – transnational organizations run by fellow elitists with the power to impose rules locally. Conversely, it was TR’s nightmare – talking shops that allowed small states to dictate to the great powers.

How do we escape the straitjacket that functionalism has become? First, current agreements must be revised or, if necessary, abrogated to narrow the scope of delegation, reduce bureaucratic power and recognize great power interests. Instead of being vehicles to achieve a fragmented form of world government, international agreements and agencies could return to the kind of transparency and limited goals that found public support in the past. Free trade pacts should drop private dispute resolution tribunals and any rules or decisions should be subject to prior public notice and comment before becoming final. The World Trade Organization should be converted into simply a arbitral body for resolving trade disputes voluntarily submitted to it by member states. In the alternative, the US should consider withdrawing to develop Its own tariff and trade treaties that preserve national security. Since the euro is one of the EU’s most popular programs, the EU should consider shrinking to become simply a monetary and customs union.

Reviving functionalism’s methodical and limited mechanisms would find favor not only in the US and the Western world, but also among the newly developed nations guarding their own recently- won sovereignty. The next post will show how their nationalism is driving international relations in the 21st century.