No sensible man will advocate our plunging rashly into a course of international knight errantry;…But neither will any brave and patriotic man bid us shrink from doing our duty merely because this duty involves the certainty of strenuous effort and the possibility of danger.

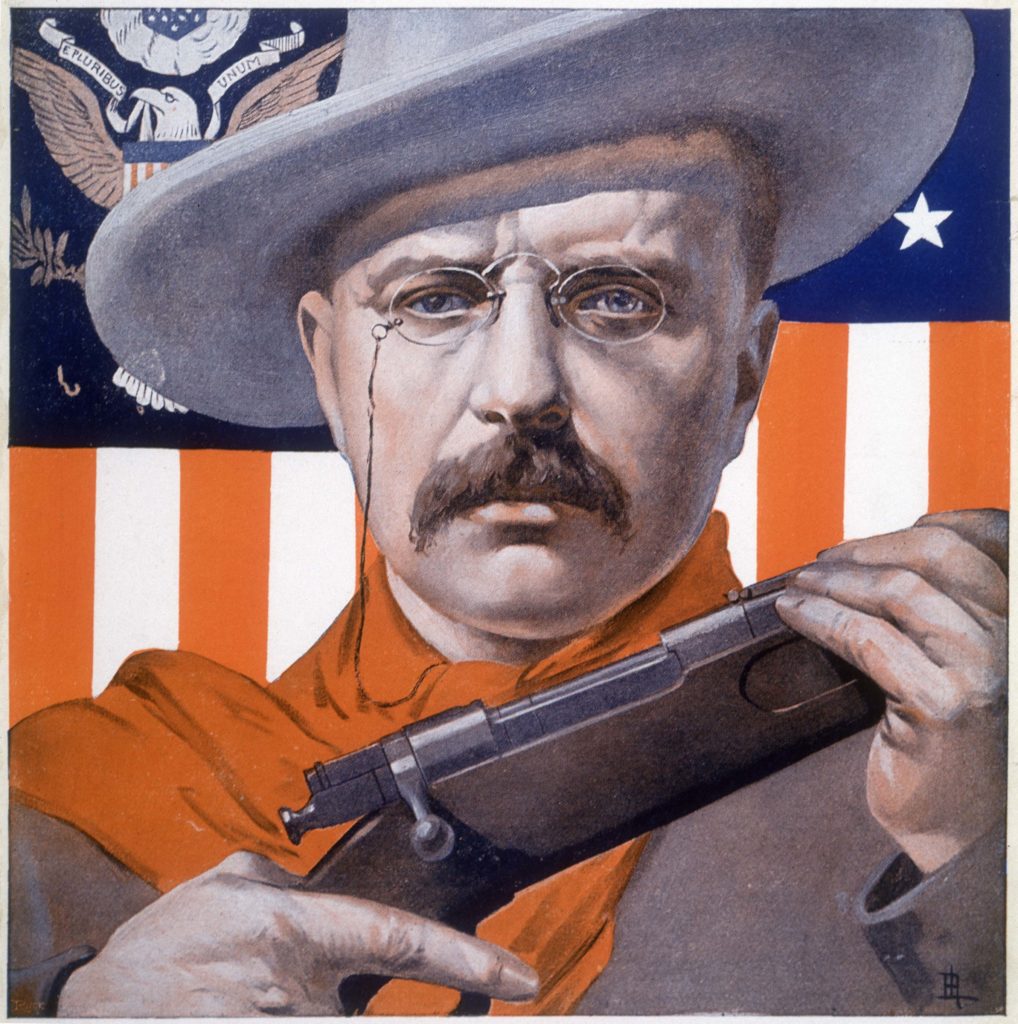

Theodore Roosevelt, America Part of the World’s Work, February, 1899

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a pivotal moment in modern European history. The feared Russian military juggernaut that spawned one of the most successful military alliances in history has now been proven to be a shadow of the threat it was supposed to be. Moreover, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s recent comments about using the war to further weaken Russia means it will continue to bleed arms and men in a long war of attrition, absent escalation of the war by the use of WMD. The shock of the invasion has also prompted Western Europeans to finally start to step up in the defense of their continent (see this video about the impact on Germany). The US should harness their new-found resolve to end its unconditional commitment to the defense of Europe and to transition NATO to a European-only alliance.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) began as a stopgap measure to protect a socially and economically prostrate post-WWII Europe from the very real threat of a Stalinist Soviet Union. Today, Western Europe has an economy that is 10 times the size of Russia’s and a larger military (for more background, see the analysis by Prof. Stephen Walt in this article). Britain and France are also nuclear powers and are capable of expanding their strategic capability to adequately deter a Russian nuclear threat. The likely addition of Sweden and Finland to the alliance will add Swedish armaments and Finland’s experience to the alliance. It also extends the NATO ‘s borders with Russia and forces it to dilute its force strength along that border.

In contrast, Russia’s failures in Ukraine shows its military currently lacks the capability of mounting a complex operation on a broad front. It will take years for the Russians to learn the lessons of these failures and it is not clear that their sclerotic political system can do so. Thus, the only likely real threat to Western Europe in the next five years would occur on a much narrower front such as the Baltic states, which could be defended by the current European membership plus the new Scandinavian members.

In fact, Europeans already have such an alliance in the European Union. The Treaty of Maastricht creating the EU has a counterpart to the Article 5 of the NATO treaty, which requires members to treat an attack on one member as an attack on all. Specifically, Article 42.7 of the Maastricht Treaty says

If a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power, in accordance with article 51 of the United Nations charter”.

https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_article_427_an_explainer5019/

Thus, the real purpose of NATO is to commit American troops and potentially our own homeland to the risk of defending Europeans.

This commitment dilutes our ability to respond to more direct and immediate threats. First, we have serious domestic social and economic needs that demand our time and attention here at home. Moreover, as both a Pacific and an Atlantic power, the United States has crucial geopolitical interests in Asia as well as in Europe. No institutional equivalent of NATO exists in Asia to counter the challenge of China and North Korea. Those security threats will have to be managed with an active diplomacy involving the Pacific Rim nations and India. Finally, we must address threats in our own hemisphere where China is seeking influence and immigration from failed states in Latin America is threatening American opportunity here at home.

It will take at least five years for Europe to build its defense capability to the point where it can defeat a Russian attack even on a narrow front. The U.S. should increase the number of troops in Europe to prevent Russian intimidation during that transition. At the same time, we should announce our intention to end our Article 5 defense commitment as part of a restructuring of NATO. After the five-year transition, American troops should be withdrawn from Europe and reassigned to other potential threats.

While Theodore Roosevelt called America to fulfill its duties at home and abroad, his caution against engaging in “knight-errantry” calls us to stay focused on the proper priorities and live within our national means. The US formed NATO to meet a critical post – war duty, but it is now fulfilled and it is time to should move on to address new duties and challenges.