The 2016 election ushered in a realignment of the political culture from a debate about big vs. small government and social issues to a one between globalism vs. nationalism. Aspects of those old debates remain, but they are now best understood as a clash between globalist elites ideologically committed to free trade, immigration and relaxed social values versus those who believe that stable families and the preservation of a national identity and the American Dream are more important. The attached article from 2016 is thus still relevant, if simply because it explains why approximately 40% of the electorate remains devoted to President Trump in spite of his obvious personal failures.

Politics has become more caustic because neither side fully recognizes this new alignment and the realistic legitimacy of the other side of the spectrum. To avoid this reality, media and governmental elites obsessively recycle the old debates much as the politics of the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century degenerated into recycling old arguments about alcohol temperance, immigration, and responsibility for the Civil War (Rum, Romanism and Rebellion).

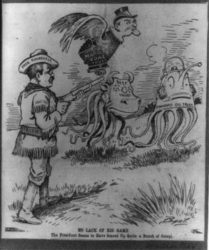

The rise of the Populist Party in the late 1800’s forced economic inequality, pernicious market power and the resulting crisis in democracy to the front of the debate. Eventually, the confrontational populist approach gave way to the Progressive Era, of which Theodore Roosevelt was a leader.

Donald Trump clearly is not that leader. However, his election will hopefully open the system to a new more constructive approach to the same kinds of issues that exist today. Whether this will require a new political party or an ideological shakeup of the current two parties still remains to be seen.

http://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2016/03/08/the_25-year_tide_that_gave_us_trump_129902.html