In the writings of our historians, as in the lives of our ordinary citizens, we can neither afford to forget that it is the ordinary every-day life which counts most; nor yet that seasons come when ordinary qualities count for but little in the face of great contending forces of good and evil, the outcome of whose strife determines whether the nation shall walk in the glory of the morning or in the gloom of spiritual death.

Theodore Roosevelt, Speech to the 1912 Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association

During the 1980s, a Texas history professor working in the UK encountered an African-American serviceman on the street seeking directions to a local English pub. He walked him to the local watering hole and ended up talking with him for quite a while before they parted ways. He later realized that such camaraderie would have been much less likely if the same circumstances occurred back in the States. Nevertheless, he began to wonder what made these two Americans feel comfortable with each other despite their different ethnicity and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Thus begins the book “Americans” by Professor Edward Countryman, which explores what truly makes the American experience exceptional. He first recognized that different American races and genders have had different histories within the broader sweep of the nation’s past. At the same time, they also shared common challenges and responded to them in uniquely American ways.

For most of our history, these differences and even the basics of our history, were relatively unimportant to the average American. When Henry Ford said, “History is bunk”, he expressed, however crudely, the attitude of most Americans that believed our history was in the future, not the past. We were still such a young country and so focusing on our past appeared useless. This attitude formed the basis of the concept of the American Dream and allowed the nation to absorb a variety of nationalities, though at the cost of ignoring the fate of African-Americans, Native Americans and women in that same history.

It all changed in the middle of the twentieth century, when the civil rights and feminist movements forced these different American histories to the attention of the rest of nation. Suddenly, America had a history relevant to today’s issues and thus worth studying and debating in the public realm. Sadly, the debate has focused on those differences and deepened the divide among Americans.

It did not have to be this way. Prof. Countryman’s book recognized and recounted those differences but spends most of its energy finding the unique experiences and attributes that make those groups American. It begins with the most basic experience – survival. While colonial records are incomplete, those we have suggest that whites, African Americans and Native Americans died at roughly the same rate in early American history. They may have died from different diseases, but they all had the experience of trying to cheat death in a new and hostile environment. He moves on to cover how African American freedmen acquired the same entrepreneurial spirit as whites. He recounts the history of Cherokee resistance to the forced relocation of the Trail of Tears by remembering they used a uniquely American tool as part of their resistance; namely, they filed a lawsuit, Cherokee Nation vs. State of Georgia. While they lost at the Supreme Court, the resort to the courts to invoke a right potentially found in the Constitution was a response that could only occur in the America of that time.

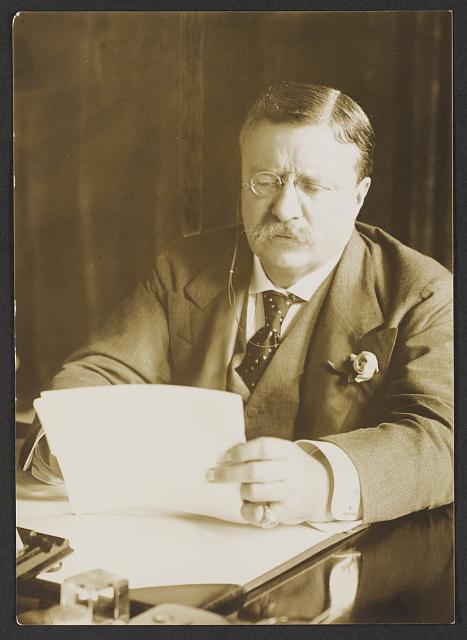

Instead of highlighting the common experiences of Americans, our media and government leaders have concentrated on the differences our history created and thus courted the same civil divisions that have led other nations down the path of ethnic and sectarian civil war. This has led to a war of histories as approaches like critical race theory clash with expurgated narratives that ignore the fact of those differences. A true American bridge leader like Theodore Roosevelt who appreciated the importance of history and was well versed in it would recognize the dangers posed by this debate and forcefully and eloquently called Americans to see their common values and experiences as the solution, not the problem, to resolving past and current injustices.

Sadly, our current political culture stokes division rather than national unity. The reason lies in two ideologies that rose to dominate our national political culture during the tumult of the middle to late twentieth century.

Next – The Decline of Community Spirit