Conservation means development as much as it does protection. I ask nothing of the nation except that it so behave as the farmer behaves with reference to his own children. The farmer is a good farmer who, having enabled the land to support himself and to provide for the education of his children, leaves it to them a little better than he found it himself. I believe the same thing of a nation.

Theodore Roosevelt, The New Nationalism, August 31, 1910

Score

Biden +.5 Trump -.5

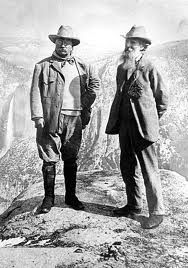

The two men pictured above represented different conservation philosophies reminiscent of today’s environmental movement. Unlike Roosevelt, John Muir believed that conservation and development could not be reconciled. Despite Muir’s famous overnight camping trip with TR in Yosemite Park, he voted for William Howard Taft in the 1912 election. Muir eventually went on to found the Sierra Club.

The contrasting philosophies of TR and Muir are reflected in the environmental approaches of Biden and Trump. However, in the end, their policy differences largely even out.

Climate Change

The differences here could not be more stark. Trump’s denial of climate science would have met with nothing but scorn from Roosevelt, but Biden’s elevation of the Paris Accord to totemic status despite its wholly voluntary nature would also have met with his disapproval (see my post “Theodore Roosevelt and Climate Change”). This earns Trump a -.5 while Biden receives a +.5.

Environmental Regulation

The Trump Administration embarked on a campaign to spur economic growth by rolling back environmental regulation, especially regarding climate change. In the process, they threw out a lot of long-standing rules that provided important protections. For example, there was no need to relax auto emissions standards that were not affecting car sales but reduced our gasoline consumption. The withdrawal of rules limiting toxic air emissions from major industrial polluters will expose hundreds to mercury and other known hazardous air pollutants. These unnecessary rule changes mean the Administration deserve a -.5

Biden would restore both the necessary rules, but pursue its climate agenda through more rule-makings similar to those of the high-handed and elitist Obama EPA. This would likely be a net drag on the economy and so earns Biden a- .5 as well.

Parks and Public Lands

Here in Montana and the West, we have a love-hate relationship with our parks and public lands. We love the spectacle and the solitude of the wilderness but resent the arbitrary limits on agriculture and other uses imposed from Washington. For example, the Wilderness Act of 1964 allowed the federal government to temporarily designate thousands of acres off limits to even some recreational use for decades. The Trump Administration decided it was time to finalize those designations and begin to release some of the land for other uses. This caused a huge controversy and became an issue in the campaign. Biden has established a goal of designating 30% of US land as wilderness, which would potentially end this review.

Trump has generally been a friend of the parks system, vetoing an attempt by his Interior Secretary to raise the entrance fees to national parks to $70. He also signed the Great American Outdoors Act, which dedicated $2 billion per year to rebuilding park infrastructure (see this post for more). However, he also has reduced the size of some new national monuments previously established by President Obama.

Both Trump and Biden earn +.5 scores on this issue.

Conclusion

Conservation was dear to Theodore Roosevelt’s heart precisely because he loved America and the beauty of its land. A true American nationalist would seek to protect that beauty for both the present and future. Trump’s denial of climate change hurts his standing on the subject, while Biden’s commitments to the Muir wing of the environmental movement suggests a potential radicalism on environmental regulation and public lands that would stifle development. Instead, the next administration should adopt the practice of Roosevelt’s farmer and seek to responsibly reconcile the many competing uses.